Active Mind, Creative Spirit

What’s in an Image of History

This weekend was the Kenmore Camera Expo at the Lynnwood Convention Center. One of my stand-by events that I’ve attended since inception in about 2007. The keynote was particularly interesting this year. A White House photographer since LBJ and Nixon, he had full, unrestricted access to Ford and created some amazing images from that time. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his work in the early 70s.

I need to back up here and acknowledge that this sort of photography was never of interest to me in college. This is what everyone else was shooting in my college photo classes – current events, random, newsworthy happenings of the world. It was the reason I stayed in fine art photo school instead of b-lining for photojournalism. For instance, a group of my college photo classmates both demonstrated against and shot photos of the Minneapolis trash incinerator when it was built and put into production around 1990. That kind of stuff. Stuff that might become history. And it’s what never appealed to me. I am kind of an anti-historian… or, call me a late adopter. Someone who does better at looking back at events to see what happened rather than deciding how big a deal they are at the moment. But I am moved pretty deeply by historic imagery from moments in our historical past, so this presentation really affected me.

I spent two hours listening to stories while David Hume Kennerly flipped through a selection of his photos. And it wasn’t the photography that inspired me, or even the people he shot, it was the fact that he had knit himself into history as a photographer. His images are the ones that have burned themselves into our mind’s eye when we think about recent history. Not just politics, but some of our sports heroes falling from grace, or music icons when they were young. He began “This one is…” a lot, followed by a story from the inside.

He had full security clearance to be in the room during top secret negotiations during the Ford Administration, and he took full advantage of that. That section began with images of President Ford moving into an emptied White House, dichotomies of American people of the time, and of course this indellible image. He took that photo. He’s been on the cover of Time more than 20 times. He told us of the time he spent (over two years) covering the Vietnam War from within, and then told the story of covering Jamestown. He said that even after being in the middle of things in Vietnam, Jamestown was the one assignment that gave him nightmares.

Everything he relayed spoke not of photography itself, but of the way he dealt with people in his midst. He photographed Sadat at Giza and told how working with a personality as strong as Sadat’s (right after the Sinai talks) led to a photo like his. And his iconic image of Betty Ford dancing on the Cabinet table. Kennerly explained that this happened at a time when women hadn’t filled many seats on the Cabinet (one or two to that point). Kennerly found her sitting at a window in the Cabinet room, looking out onto the lawn, perhaps imposing her presence as a female in the male-dominated business space. She saw him and said, “I’ve always wanted to dance on that table,” then, according to Kennerly, she (with only him in the room) kicked off her shoes, and did just that. According to Kennerly, President Ford wasn’t so pleased when he saw the photos much later, but the First Lady loved them.

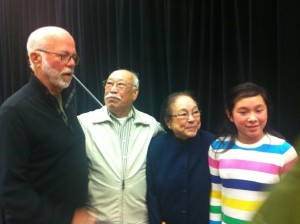

One of the attendees of the conference yesterday was the man who hosted Kennerly while he was in Vietnam all those years ago. They had only been reunited days ago and as Kennerly introduced him and had him stand, the crowd acknowledged him in applause. I caught some of their conversation after the talk when they were agreeing to meet up, “If only there was a pho gau place around…” I interrupted long enough to point them to the one ten steps outside the convention center where I’d just had lunch.

Other photographic talks I’ve attended have been full of beautiful imagery, information or are technically fulfilling. This one did something else. It placed a historical figure in front of me and allowed him to tell history’s stories from behind the lens.