You might think I know a lot about Nepal because I have been there a few times. That’s not the reason. I know many climbers (famous and not) who know much less about Nepal than I do. It’s because I, like an annoying little mouse on a squeaky wheel, I ask questions incessantly. I am endlessly curious about everything around me and I have a deep need to know why, what, where and how. Dherai dhanybhad (many thanks) to everyone who has weathered my incessant questions. Thanks to my patient Nepali friends, I have a deeper understanding of a culture that I never even knew about until I was in my 40s. I understand some Nepali, too (added bonus). It’s endlessly entertaining for me, when Nepalis pass me and greet me in English, “Hello, how are you doing today?” and I can answer back in Nepali. It’s not common. It’s my curiosity. And it’s not just Nepal. I drilled our guide in Bali the same way. I insisted on sitting in the front seat while he was driving (there were 8 of us) and pummeling him with all varieties of queries. I want to know everything. What’s that fruit, how do you prepare that veggie? Why are some steps black, others white? What do you call those round red peppers? Where do the building materials come from to make the houses way up there? Where does that water come from and where does it go? Can I drink it? Do they hire a home builder or build their own home? Do they really carry cement on their backs up there? (answer: yes.) See it’s interesting!

A really cool thing happens when you show that much genuine interest. Once you’ve spent enough time with them, engaged in learning about them, people start telling you their own stories. They share their own personal experiences within their culture. So here is my favorite from my last trip to Nepal. I was walking alone on the first 3 days of the Annapurna Circuit. Well, alone except my guide and my porter. So, not alone at all. I wanted to see some different mountains this time. I knew who I would ask to guide me…

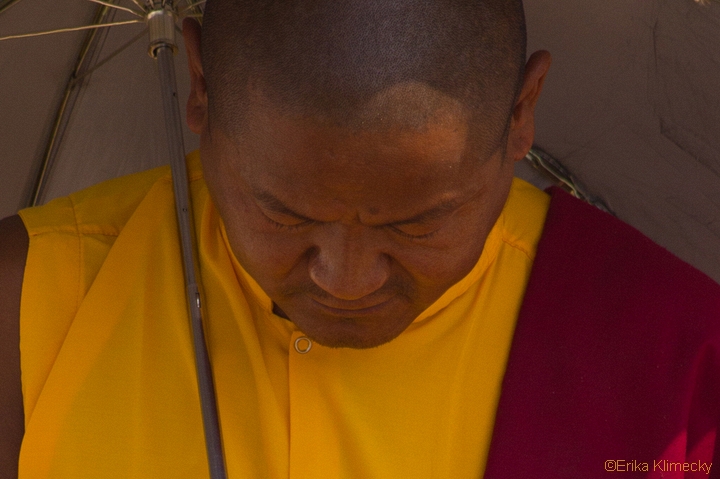

Tsering, my guide for the last 4 days (and last time I was here) used to be a Buddhist monk (lama). Tibetan people and Sherpa people derive from the same root, and they have similar language and culture. Most Sherpas follow the teachings of the Dalai Lama, since Sherpas are traditionally Tibetan Buddhist as well. Tsering studied as a lama in India before falling ill and having to quit the monastery. When he healed he became a mountain guide near his home village – the Himalayan foothills below Mt Everest.

In 2013 Tsering led Mary Beth and I for 8 days, through the villages of Solu and up to Tengboche Monastery, the highest monastery in Nepal (12,700 feet elevation). It’s a pilgrimage point for many Buddhists. Along the way, we visited 14 monasteries, culminating at Tengboche, where we witnessed the monks chanting at dawn. My heart soared when Tsering, who sat on the floor next to me, joined in, adding his voice to the monks’ as they chanted in deep guttural tones. When it ended, we exited the monastery to the sun rising on a perfect view of Mt Everest. It was an experience I will never forget. On that trip, Tsering often stopped along our path and read the traditional Tibetan script that had been carved into mani stones on the sides of the roads, and near holy sites. Because of his background as a monk and resulting connections, Tsering was able to get us into several monasteries that were closed to the public.

Now I should tell you that Sherpa families do not name their own babies. They take them to a lama (monk), preferably a Rinpoche (like a bishop) in their village to receive a name after a baby’s birth. This is considered auspicious and brings good luck, to receive a name from a rimpoche, as it is thought to bestow health and good tidings on the baby. (Sidenote: Sherpas are given two names: one for the day of the week they are born, and one for virtues.) Traditionally the rimpoche chooses a name based on the virtues the rimpoche sees in the child at birth. An example would be “Tuesday Long Life” or Mingma Tsering. As you can imagine, with only 7 days of the week, there are a lot of Sherpas named Tuesday. They often go by nick names, or descriptors. I asked Tsering what his nickname was among his guide friends. “They call me Thulo dai… Fat brother,” which he announced with a grin.

Since I saw him last trip, Tsering has married and gained a daughter. As his wife went to the hospital to deliver, he called his teacher in India, from his days as a monk, to tell him about the pending arrival of his child. It’s natural to share these things with connections like that, so gurus and monks can shed blessings during prayer times.

At the same time, it just so happened that the Dalai Lama was visiting the city where Tsering’s guru (monastery teacher) was – the place in India where Tsering had studied to be a monk. (I had to extrapolate here, but it sounds like the DL visits a circult of schools and monasteries to hand down teachings to the gurus who then offer it to their students. I don’t know enough about this. Clearly I need to ask more questions.)

The guru went to The Dalai Lama, (whose given name is Tenzin Gyatso – remember that). The guru relayed the information of his student, Tsering’s baby soon to arrive, so the Dalai Lama could shed prayers in advance of the birth. A few days later, the guru reported back to Tsering: “Tell me when the baby arrives, I will deliver the news to Dalai Lama,” and so he did.

Days later the teacher sent a reply and photo through Facebook (I don’t know about you, but I kind of expected to to arrive on scrolls or something). The Dalai Lama had drawn on a sacred mat the name that this baby should be given. At this point, Tsering was so enthused in telling me the story that his descriptions and explanations broke down a bit and I struggled to grasp the full understanding. Then we both paused, rapt by the story (and perhaps walking up a hill in the Himalayas) and took several labored breaths.

“His Holiness gave his own name, Tenzin, as part of her name. Her given name is Tenzin Yangchen and it came from the Dalai Lama! This is very lucky for me!” Tsering said, his joy radiating from this high blessing. Tenzin means “holder of the Buddha dharma,” or, as a rough equivalent: keeper of the truth. Yangchen means Sacred One. “My teacher sent me a photo of this mat drawing! I still have the photo of the mat on my phone, of my baby’s name, that the Dalai Lama made. I am so happy. This is very lucky for me.” And so that is how the Dalai Lama named my guide’s baby. Definitely auspicious, don’t you think?