The words of the men on the beach rang in my head. From the moment I left, I let the thoughts affect me and they’re still with me as I stand in this space. I walked to the tree trunk with its sign, then something asked me to stay here a moment longer.

This is part two of a story. Part one is here.

A car pulled into the drive, and parked next to the office. I gave him a minute to unlock the door before I approached to engage him in conversation. After greeting me warmly, I asked him about the buildings and the location. It used to be a mill, he said. The big round building was the mill house but they rent it out for events now. I figured since they use it for events I might be able to see inside. His body was in motion before words came in answer; he grabbed the key and headed toward the large round, red building.

“Sure… there’s a long boat in there, we just blessed it this weekend.” We walked across the grounds as he described the railroad lines that used to be here, but have been pulled out from between the buildings. The ones that used to support logging on this land. And he told me about the work that the Quileute tribe plan to do to further improve the whole property.

His voice echoed inside the cavernous building. Bare wood struts reached high to hold the grand circular roof. They sloped outward and down to posts set in a circle, midway between the center of the room and the outside walls. The majority of the space was filled with a giant round wooden platform risen off the cement floor several inches. “It used to spin freely, people could dance on it while it was moving, but we decided to pin it down, so no one gets hurt.“

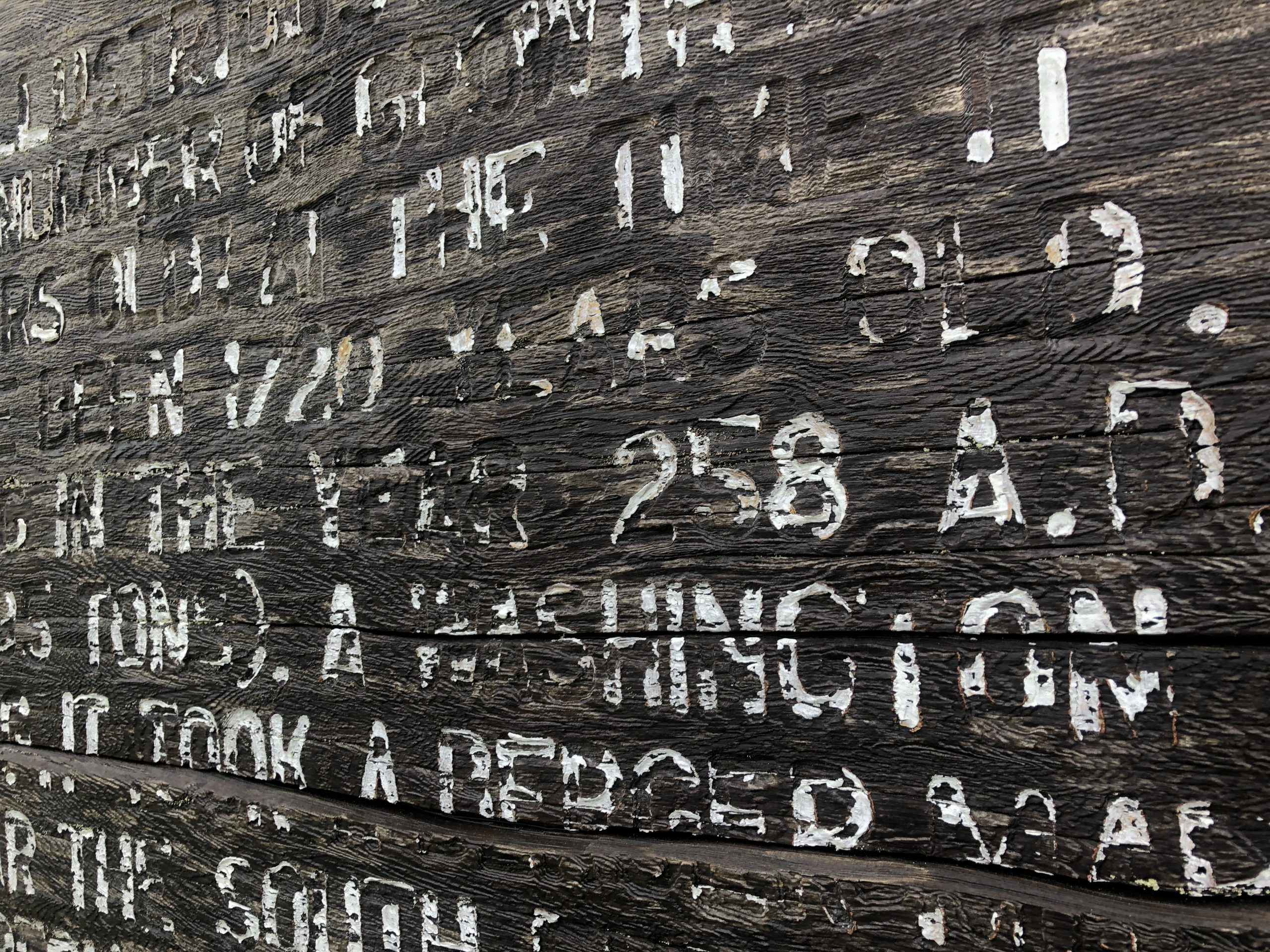

It took me a minute to figure out that the wood circle was from the original mill set up, not something they had added to facilitate celebrations. Directly before us was a long wooden canoe cut in the Pacific Northwest Native American style, from a single log. It was painted, patched with metal in a few places, and boughs of cedar still rested under the bottom of it, from the blessing ceremony.

Uniform windows encircled the round outside wall of the building. Above them were paintings depicting life and ceremonies of Quileute Tribal activities. “It’s a beautiful space,” I said, turning to see into dark, distant corners. “How many people came for the boat blessing ceremony?”

“Well this place was pretty much packed… About 400. And we have improvements planned, New kitchen, we’re gonna make the bathrooms….”

“And how big is the tribe?”

“Our tribe is a little over 1500. We mostly do weddings here, group celebrations, and gatherings. Last time we booked it we had a group come in, they covered it with hay… I don’t know what the hell…They had this thing… a ho-down… I don’t even know what the hell ho-down is, (I chuckled) … oh my God, they had fun, but they cleaned it all up. No hay left by the end. And, you know, I don’t care what people do in here as long as they clean up after. And they did.”

I walked toward the boat and around it, looking at the grain of the wood, the paint, orientation of the seats. It was a beauty of craftsmanship. “We have to get a permit to take a tree, you know.” [In order to make a canoe]

“Can I take a photo of it?” He obliged energetically. “Who did the paintings?”

“These paintings came down from the other location, over in La Push… I’m not sure who painted this one.” It was a seascape with orcas in the foreground, seastacks in back, and a long boat full of men paddling in the center.

I looked at the next painting just as he begin to talk about it. “Our biggest enemies then we’re the Makah, you know, and still are! Our ancestors, living on James Island, would roll boulders down on the boats of the Makahs when they came to attack.”

“So that’s James Island, in that painting?” He nodded, and didn’t pause when a young man, perhaps in his mid-twenties, entered and stood beside him without saying a word.

“They used to steal our women, and behead them, then throw them back, you know. They used to raid our villages.” In describing his tribe’s worst enemies, he used words that if I said them, they would sound more ugly. It seems the local tribes were at war with each other since time began. “We eventually had to move off of James Island, to the mainland, on the land nearest La Push.”

Once there was a break in his words, I smiled at the younger man and greeted him. He had no intention of interrupting the conversation until he was invited. “Oh, this is Dave.”

“Hi Dave, pleasure to meet you, my name’s Erika.” He smiled, dipped the brim of his hat, but said nothing. I directed back to my host, “And your name is?”

“I’m Leroy. Dave and I keep care of this place… Dave nodded again; Leroy continued, “But I didn’t grow up here. I’m Quileute, but I was eleven years old when the Bureau came and separated my family. We had no choice. My two sisters went to Nebraska. We older ones, three of us, went to Oklahoma. I was there for six years. They put us in a boarding school. Back then, out there, boarding school means a bad school, but we weren’t bad kids… Just, our father decided, God is going to take our dad, and left our mom with seven kids. And the BIA thought it was a good thing to do, to take us away and spread us out all over the country. They paid us $11 a month, and you know, it was hard.”

“You said you have six siblings. Where are they now?”

“All dead.” I gasped audibly.

“What about after boarding school?” I attempted a recovery. I wanted to hear more of his life history.

“We got to leave and go where we wanted, because our [collective] parents didn’t really want us to come home. They wanted us to learn from the outside world before we did come home. By that time the war in Vietnam started, everybody up and went to Vietnam. I went to school later on in my life, and while I was in school they didn’t draft me. I went to Montana after I graduated college, and had three kids of my own. I lived there in Montana, I loved it… Big Sky Country; it’s just, it’s beautiful. I call it home I have friends there because I’ve lived there longer than here.”

Leroy went back to history and land rights. “We’re still fighting them… about fishing rights now, in Congress. They’re in the north, you know.” I nodded. The Makah make local news when they exercise their rights each season by hunting a gray whale as part of their tribal ceremonies. “The Makah are a big tribe. They are claiming the whole thing, and want to chase everybody out. They think it’s all theirs. But it’s not. It’s all on paper, who owns what, it’s there in black and white in Congress.”

“Who oversaw that paperwork?”

“Our [state] governor in Olympia, and the Congress, and White House. And our tribal chairman met with the governor. They traveled together to Washington, to fight. Every tribal chair went with their governor to Congress, to fight for water and fishing rights.” He paused, perhaps thinking about his last interaction.

“Last night I got asked to coach a basketball team for this coming year. I am pushing 70… People says, ‘when are you gonna slow down,’ and I won’t slow down. Dave could probably tell you, maybe I have slowed down, I gotta really think sometimes… And I got high school kids who come in and walk with me, put up with me, take care of me, and respect me. But, if you travel up and down 101 from Aberdeen to almost Port Angeles, natives own… we own most of this. You take the Quiluetes, for instance, we owned from the Hoh river, all the way to Port Angeles. We’ve been fighting for our land for a long time. We want the beach back, we want Rialto back. For about 50 years we’ve been fighting, way back from when I was in Montana.”

“In reality, we’ve been fighting for this land forever. I think we can pray for the best of it, and pray for working together. That’s what it’s about – working together, walking together for this nation, for this world.”

He pointed up to the painting of the men in the long boat. “You know… all these guys, they still canoe, they still do their journeys… I don’t know where this journey is in this painting, we haven’t had them in a couple years, but they paddle to each reservation, and into Canada. They sometimes go 18 days, paddling, our men, on these journeys.”

“They paddle during the day, then come ashore at night?”

“Yes, each night, they ask permission to come ashore, we’ll paddle from here to Neah Bay come ask permission to come ashore from the Makah, if they give us permission, we go up to eat, stay in long houses, and that’s when ceremonies begin. Until about midnight or one o’clock they dance they sing, then they get up and go to the ocean at 4:30 and paddle the next day. Sometimes the Hoh [tribe] will come with us, and we all go to Seattle sometimes, on these journeys.”

“After the army, I got my college degree and became a teacher and coach, working with kids here. I still coach basketball… That’s been my calling. Kids keep me going. Seeing them doing the hard part without complaining, in hopes they will learn for me and respect their elders.”

Leroy said he didn’t need money to be happy. Twenty dollars and a place to get coffee or something to eat was all he needed to be the happiest guy on earth. He also said that he used to be 255 pounds, had survived 5 heart attacks, an open heart surgery. But he also talked about winning back the rights on Rialto beach. I’ll bet his tenacity is well known. I saw their sign on the left side of the beach parking lot when I drove into Rialto. He wants to set up a taco truck and a coffee stand. Why not get those tourists coming in and offer them some refreshments.

Lots of history, ideas, experiences, stories in that one man. I’m fortunate I got to listen to him speak for an hour, about whatever he wanted to say.

Bits that stuck in my memory on the rest of the drive home:

“Mother Earth is what we do. That’s what we want all of us to do.”

“I got high school kids who come in and walk with me, put up with me, take care of me, and respect me.”

“If you travel up and down 101 from Aberdeen to almost Port Angeles, natives own… we own most of this.”

I drove through that space he referred to immediately following my conversation with Leroy. The road is quiet by my city standards. Early on a Tuesday morning, the thin, curvy two-lane holds more logging trucks than passenger cars. Giant hauls of peeled tree trunks, were taken a moment ago from nearby mountainsides. They hang in my rear view mirror until I round the next curve. I’m headed home.

The color of Lake Crescent is glacial teal around the edges, just tipped, as if to tempt you to look deeper before the sun goes behind the next cloud. Dainty trees hanging over the water, are older than they appear. Light splashes on them from moment to moment – if you get a sun-streaked day. Then everything returns to sullen gray.

One comment on “Corner of the World Part 2”

Comments are closed.