I ventured west on 101 past Port Angeles, across the Elwah River, down a big hill and further into wild lands. I crossed the Sol Duc River at least four times before making the last turn to the coast. It’s the far northwest corner of Washington State, and also the lower 48. I camped there by myself for 3 days.

I arrived at my campsite in the late afternoon, dropped my gear, then headed directly to the ocean. I so love this beach. I’ve been here twice before and each time it has completely captivated me.

Giant sea stacks stand sentinel at either end of the 2-mile long stretch of black rocky shoreline. Between them, especially this time of year, the waves roll violently toward the shore, crushing stones into smaller stones with every stroke. Last time I was here I spent hours with my camera just shooting the curl of the waves. Waiting for the light to catch it just right, to reveal green and foamy blue before dashing into the bubbles below. I didn’t bring my camera this time. I spent my time sitting on the beach solo, listening to what the waves had to say.

When I first arrived, gray edges scattered across the flat white sky, casting a sullen mood. The wind was unforgiving, sending salt spray to my face, covering my lips in that familiar taste.

The power of the ocean on a windy day is unparalleled. If you ever want to feel the grandeur of the energy of mother nature, stand at the edge of the Pacific on a stormy day. The scale of this world shifts so aggressively, that I’m grasping for items of comparison – a person, a car, a building so I can grasp the vastness of this landscape.

With the overcast day, desolate beach and howling wind, I couldn’t see it any other way than a graveyard. It’s a moody place to be, when you don’t have the chatter of a group to distract you from the stark landscape.

The most staggering piece of this landscape is the skeletons. Rows of ancient trees have been turned by the tide and pushed high up onto the shore, in chaotic piles. Some are thirty-feet long, others have root balls 10 feet across, still attached to bleached trunks, as if they were discarded bones from ages long past. I found one tree trunk with a 6-foot diameter, which means it must be several hundred years old. Most certainly older than my country.

It’s humbling to stand on this beach – Rialto has long been a favorite of mine – without any distractions. I am here with only my thoughts. When the wind doesn’t overwhelm my ears, the crashing waves do. It’s luscious and fills my chest with thunder, my veins with adrenaline, my mind with poetry.

I stood for a long while next to a behemoth skeleton, wondering where it originally grew… and I thought about time. These grand trees, living beings who have lived, some since ancient times, are fallen and washed out to sea. Everything dies.

I am pondering the power of the Pacific to be able to move even one of these. There are hundreds. Now only a shadow in driftwood, some still have branches and bark, others are bleached white by the sun. Unrelenting wind, churning of waves on the rising tide, and the sentinels of history, are now laid to rest far above the high tide line. The beautiful energy speaks not in time but in repetition. The sea marks time in years far longer than our own. Wind is timeless.

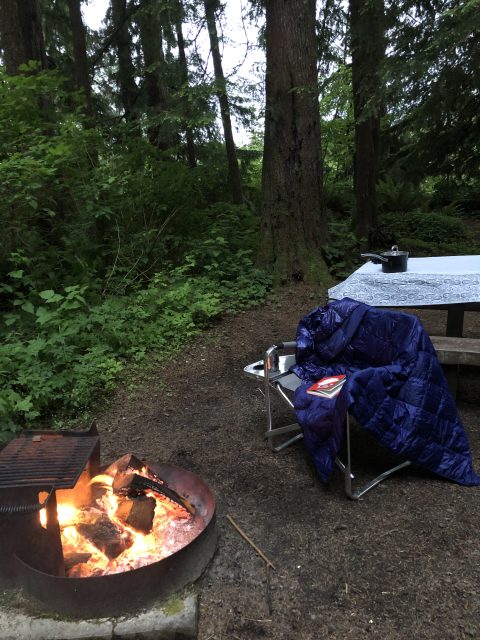

Back at camp, evening birdsong gives way to pre-dusk frog song. Everything in nature is singing. Or roaring. I think I can hear the wind and ocean waves dancing together in the distance. I’m sitting fireside, reflecting on Rialto. I’m alone except for the giant cedars around me.

The next day, I walk to the edge of my campsite. Beyond those graceful trees, down a rough trail, it opens up to the Quilayute River. There I see a lone fisherman in his metal fishing boat, pulling up nets. Once the boat is full of netting, he speeds up the river, then down, to set a new boat-full of net. The beach is calling, so I head that direction. On the way I pass a police vehicle pulled off the thin, two-lane road, along side the river. I stop and ask him if it’s legal to net fish this river. He lets me know it’s the First Nations fishing river, and he offers the name of the tribe. It sounds similar to the river name, which makes sense.

I’m back on the beach again. Sitting completely still in the graveyard of trees. I have so many feelings about them; with light spatters of rain, the feelings are still mostly melancholy. I spend most of the day just being in the space, walking the beach, sitting on, under, around the trees. I ford a river and hike to the far end of the beach, where one of the giant sea stacks has a hole in it that you can walk through when the tide is low enough. Instead, it’s high tide, so I hike to the top of the hill and sit solitary, taking in a panoramic view from above.

On my last morning, after I left my campsite but before I left the area, I drove to Rialto Beach again to see the ocean one last time. But almost two days later, I’m familiar with the hidden paths between the bones. I work my way from the parking lot through the jumbled mess of skeletal giants, and onto the rocky beach one last time.

It’s a -2.8 tide – that’s really low, so I consider staying to re-walk the mile and a half of Pacific shoreline I walked yesterday. I would see the tide pools with so much water gone; but I’m not drawn to stay. I can’t say what it is, but something’s pulling me to go. I’m feeling the desire to move on, more than desire to share tide pools with the trickle of tourists who are walking the beach already, an hour in advance of the lowest tide.

As I reach the parking area, two First Nations fellows pass me on their way to the far end of the beach. The more gregarious one asks, “Are you leaving so soon? It’s about to be a good tide…” I relay that I’ve been here for two days and it’s time to go.

“You’re not going to stay for the tide?” I shake my head. He pauses only enough to reveal a ray of sunshine in his gentle smile. “There’s nothing more important than what you got right here.” He looks over his shoulder at the waves. The wind tugs the tops off of each of them sending salt spray toward us.

My heart tugs back, knowing he’s right. I smile and head toward my car. They head toward the hole-in-the-wall at low tide.

A half hour later I pull in to the community buildings of the Kit’la Center. It had caught my eye the day I came in, and I made a mental note to stop. No one has opened the office yet. It’s only 7:40 AM.

I walk the property I spy a grand, round building, labeled, Quileute Roundhouse. I’m curious about the grounds, and it looks inviting, so I spend some time wandering around.

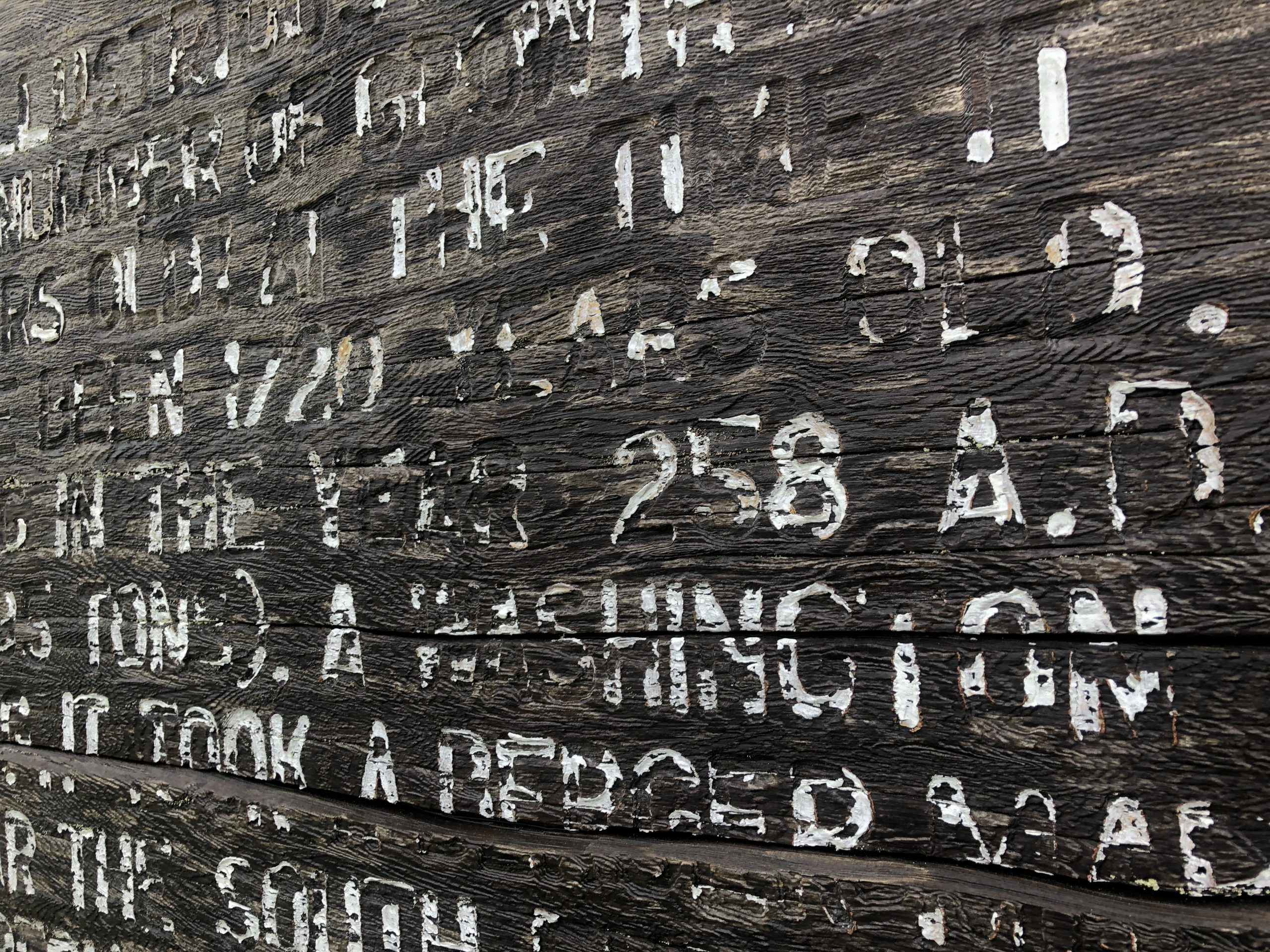

While deciding whether to stay, I notice a wooden sign, five feet high, that I can’t quite read. It’s faded and old enough I can’t tell immediately if it’s even written in English. White paint has been worn away from most of the letters; I struggle to read the text. Directly behind it lays a huge section of an old growth tree that was cut down in 1978. At the time it was cut, it was estimated to be 1720 years old. The sign explained that the tree most likely began growing in the year 258 AD.

I love when history like this is preserved for us, in hopes that we may never repeat the same trespasses, but it stabs my heart. In a flash, I’m in my head, standing back on the beach with the dead ancient trees, feeling their pain again.

This is part one of a two-part story. Part 2 of this story is here.

One comment on “The Corner of the World”

Comments are closed.